Telling Your Story

Summary

- We use stories to understand the world around us.

- If you don't tell people stories about your work, they'll create the stories themselves, and they won't do justice to what you've accomplished.

- The classic Three-Act Structure used in books, TV, and movies is a powerful tool you can use to communicate your work and the value you've brought.

Hot Take

I entered the workforce thinking business was a meritocracy: if you do good work, you’ll be recognized and rewarded. Eventually, I came to see things differently. There are many reasons the “meritocracy” theory fails, but one big one is simple: if folks at senior levels don’t know you, don’t know what you’ve done, or don’t know how you’ve accomplished those things, they can’t recognize, reward, or even help you. Yes, there are very real problems with bias and manipulation, too… but the biggest reason the workplace isn’t meritocratic is just physics: people can’t reward work they don’t know about.

Therefore, being able to tell a story about your work is a vital career skill. In this article I'll explain a classic tool used by professional writers to structure compelling stories.

The Importance of Storytelling

Storytelling is central to our psychology as humans. We love movies, TV shows, video games, novels, and more—all of which use stories as entertainment. We also tell stories about ourselves and others, not just in verbal conversations, but also in our private inner monologues. Stories surround us, and we use personal stories to explain the world and guide our actions.

The stories we tell about each other are often wrong, though. Maybe we didn’t have all the facts, or maybe the “facts” were wrong: we misinterpreted something we saw, or we trusted someone else’s story that, itself, was misinformed. You see this on social media all the time: someone tells a story, people start reacting to it. A few hours or days later, we find out the origin of the whole thing was a misunderstanding, or even a fabrication.

I’m not writing about politics or social media today, though; I want to talk about how you tell your story. This is important for career development because your story is a big factor, sometimes the biggest factor, in how others perceive you, your capabilities, and your performance. If you don’t tell your own story, others will tell it for you, and you may not like how those stories portray you and your work.

Storytelling ties directly to your career. At tech companies (and many non-tech ones), promotion decisions are typically made by a small group of senior people who review and discuss the candidate and their work before deciding whether they will recommend promotion or not. As a promotion candidate, you are often asked to provide a written explanation for why you should be promoted, either directly or through your manager. The reviewers and the process they follow varies from one company to another, but conceptually they all read and listen to “stories” about you and consider whether those stories sound like they’re about someone who’s ready for the next level.

Besides supporting promotion cases, personal storytelling has many other uses, too. Here are a few examples:

- Your resume is essentially a story about you and your work.

- A large portion of job interviews consists of you telling stories about your past work or how you would do future work.

- Onboarding new team members involves sharing stories with them about the team, its work, and how they’ll become a part of it.

- Conveying a vision for your or your team’s future and how it will be better than the present is fundamentally about creating and telling a story.

In all these cases, you need to do what the folks in public relations call “controlling the narrative”. You need to tell your story in a way that resonates with your readers so they don't create their own, unhelpful, narratives.

With the benefits of storytelling in mind, let’s explore how you can create a compelling story of your own.

How Professional Writers Tell Stories: The Three-Act Narrative Structure

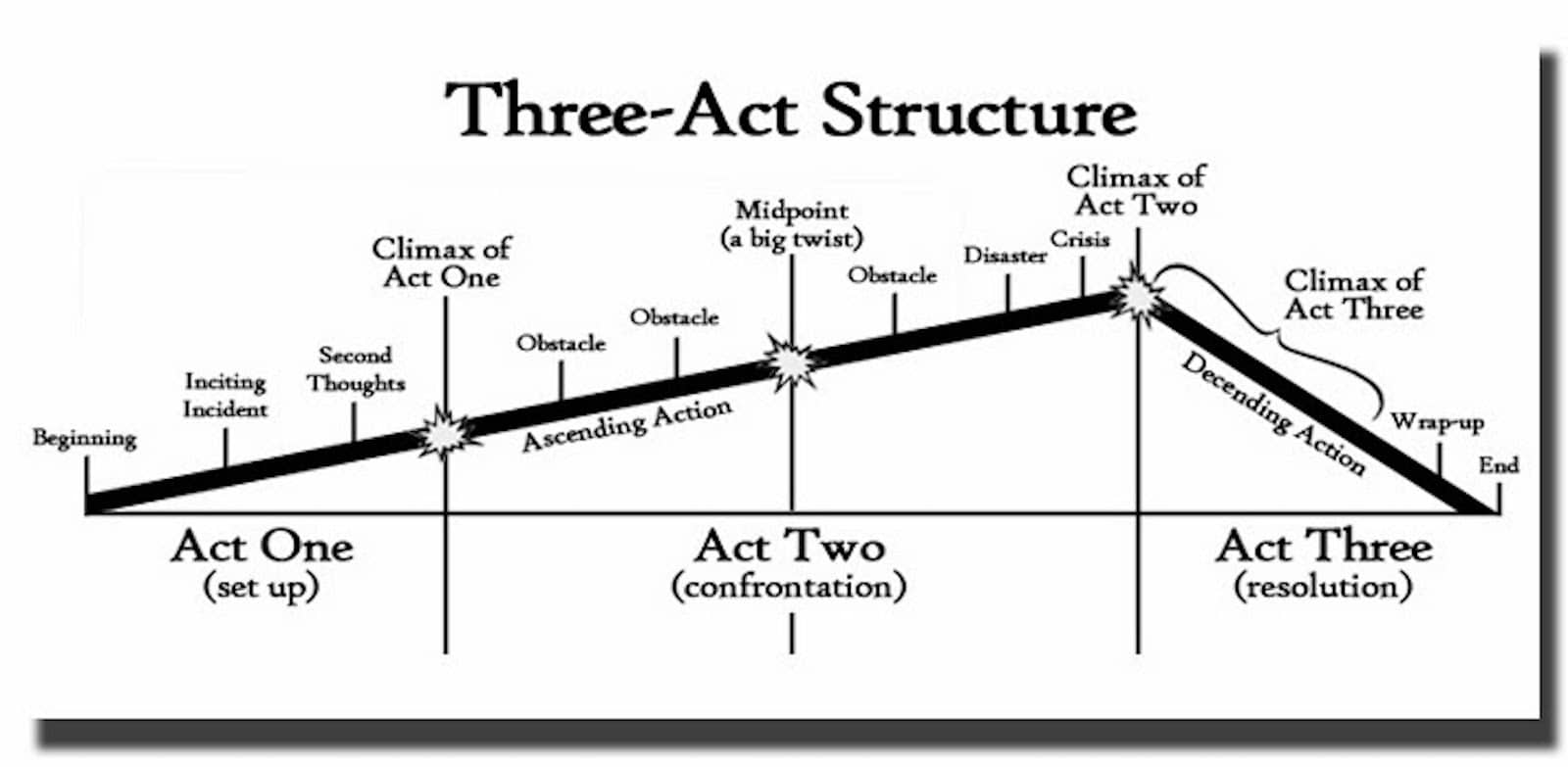

People have been telling stories forever, and there’s been no new “science” to how good stories are told in ages. Thousands of years ago Aristotle talked about how all stories should have a beginning, middle, and end. This “three-act narrative structure” has been formalized over the centuries, but never really improved upon. Today, writers are taught to tell their stories using this classic “Three-Act Structure”:

- Act I: Setup. This act introduces the characters and setting, including an “inciting incident” that sets the story in motion.

- Act II: Confrontation. The story advances as the heroes face obstacles with steadily rising stakes.

- Act III: Resolution. The events in the story reach a climax and are wrapped up.

Here’s a video explaining the Three-Act Structure, using examples from popular movies. As you watch, don’t worry about remembering the details; just think about how you can use this to tell your personal story.

Applying the Three-Act Structure to Your Work

Let’s see how to apply this structure to a personal story about your last big project. The same Three-Act Structure used in books and movies works here. You (probably) won’t be writing book- or movie-length stories, but the same Setup, Confrontation, Resolution structure can effectively convey your contribution and the value of your work. You can create a story about your project with you as the protagonist!

Act I: Setup—The Situation Before You Began

Begin by painting a clear picture of the situation before you took action. What problems existed? Why was that bad? Use specific metrics wherever possible. For example, perhaps the team was missing 40% of their deadlines, and schedule slips were getting worse. If others tried to solve these problems before, briefly mention those attempts and why they fell short. This context helps readers understand the problems’ significance and the challenges you faced in solving them.

Act II: Confrontation—Your Actions

Explain how you solved the problems outlined in Act I. Be specific about your actions and contributions. Avoid vague phrases that make you sound like an observer: don’t say things like “I oversaw…”, “I helped…”, “I participated…”, or even “I was responsible for…”—phrases like these give the impression you weren’t actively involved in achieving results.

Instead, use action verbs that clearly convey what you did, such as “I designed…”, “I implemented…”, “I decided…”, “I persuaded…”.

Also explain why this project was hard. Did you have to deal with tight staffing constraints? Organizational resistance? Unexpected technical complexity? You had to overcome challenges to achieve success; what were they, and how did you overcome them? Include key decisions you made and how you influenced others to support your approach.

Just like in a book or movie, Act II should take up around half the words in your story. It’s where all the “action” takes place.

Act III—The Results You Delivered

Act III answers an important question for readers: “so what?” Think of when Frodo destroys the One Ring in the Lord of the Rings. If the story ended there, we’d wonder what happened to Middle Earth. Yes, the ring was destroyed, but did that really matter? What about all those orcs and other nasty villains? Many of Frodo’s friends had been in danger... what happened to them? How did the War of the Ring affect Frodo’s home, the Shire? Act III resolves the confrontations of Act II.

Likewise, your story about your project can’t end with the last milestone. Wrap things up for readers by telling them why the work you did in Act II matters and why they should care.

It’s important to use specific, concrete metrics here. Offer metrics like “I reduced deployment time to four hours” or “the team now hits 95% of deadlines,” but that’s not enough. I can imagine some readers asking “why should I care that you reduced deployment time?” (I can imagine this because they’ve asked me that, repeatedly!).

To help your readers understand the impact of your work, tie it to things they care about, usually money or business objectives. Say things like “I reduced deployment time to four hours, saving $50K per month in labor costs”, or “the team now hits 95% of our deadlines, enabling our business to meet customer commitments, increasing our NPS score from 30 to 60”.

It's also useful to name specific stakeholders who can verify these improvements, such as "Jane Smith, VP of Engineering, cited this work in her quarterly review."

Which Stories Should You Tell?

Not all the stories you could tell will help you. Some aren’t engaging or interesting, and some won’t improve people’s opinions of your capabilities.

If the story’s purpose is to justify a larger budget or more staffing, tell an interesting story that showcases your judgment as a responsible steward.

If your story is to help you get a job (e.g., for a resume or an answer to an interview question), research the requirements for the job, the work of the business, team, and manager. Then, tell a story that shows you excelling at the capabilities they need.

If the purpose is to make a case for a promotion, tell a story showing you exercised skills required at the next level and delivered results with next-level scope. You have many stories where you did a job well-suited to your current, or even a lower level, but the promotion decision-makers don’t care about that work, even if it was necessary and valuable. They’re not deciding whether you’re doing well at your current job; they’re deciding whether you’ve shown you can do a good job at the next level.

Regardless of your story’s purpose, focus on what’s important to the readers, and limit yourself to telling them stories that highlight those points. It’s powerful to say: I saw problems you care about (Act I), I made a plan and executed it (Act II), and here are the results I delivered (Act III).

Illustrations for Your Story

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and we can put that to good use in storytelling. A book with artwork, illustrations, or photos is more engaging than one without. When it comes to telling personal stories about your work, your illustrations are the “artifacts” of your work that you include in the story that give the reader a clear picture of your work’s quality and impact.

In Act II, if you say you created a strategic plan, include a link to the plan. This way, readers can quickly click through, see it, and say, “yeah, that’s an impressive plan”, then go back and continue reading your story. When you mention a slide deck you created that the sales team used to close a deal, link to that deck. Illustrate your story with hyperlinks.

Be careful, though—you only have your readers’ attention for a limited amount of time. If you give them a sea of so many hyperlinks they can’t click them all, they’ll only click a few... and chances are, they won’t be the most impressive ones. You need to be selective in what you link to.

Generally, people will take your word for it that you held a monthly meeting—they’ll believe you without needing to verify the meeting minutes! Link to artifacts that are:

- Impressive

- Quickly understandable by non-experts

- Confirm that what you’re saying is true

An Example

Let’s tie this together! Please allow me to introduce you to Anika (a fictitious person modeled on real people I’ve worked with). Anika joined a team that was dragging down company sales and turned everything around. When it came time for her annual performance review, her manager asked for a list of her accomplishments. Here’s what she gave her manager:

• Helped achieve improvement in milestone adherence from 0% to 85% over one year.

• Implemented Scrum practices to improve delivery accuracy.

• Facilitated a reduction in sprint duration to 5 weeks within a year.

• Contributed to a sales increase.

There are some big improvements there, clearly… but it’s not clear what role Anika played, how significant any of this was, what was challenging about it, and frankly, it’s boring. No one will remember it, or her.

Fortunately for her, though, Anika is a regular reader of the Order From Chaos newsletter. After reading the article you’re reading now, she decided to rewrite her accomplishments as a story using Three-Act Structure, action verbs, and keeping the “why should I care?” question in mind. Here’s what she came up with:

At the end of Q1, the Stiletto team faced a crisis. Sales were falling, and the team was partly to blame. They missed deadlines, causing a ripple effect on downstream teams, hurting sales and frustrating everyone. Stuck in old habits, they overpromised and underdelivered.

Anika joined the team in Q2 and started small to overcome their skepticism. She persuaded the team to try their first-ever sprint planning session, a key Scrum practice. Early success sparked curiosity, and Anika seized the moment. She introduced the team to another Agile practice, retrospectives, which empowered the team to identify workflow improvements they could make. Data became Anika’s ally, showcasing sprint-over-sprint progress and winning hearts and minds, not only her own team, but downstream teams as well. Gradually, the team embraced new practices, refining their estimates and improving their workload and work/life balance.

With Anika’s guidance, the Stiletto team’s performance surged. On-time delivery soared from 0% to 85%, and sprint cycles shortened from 8 weeks to 5, enabling the team to become more adaptable to changing needs. As a result of Anika’s efforts, customer satisfaction rebounded, fueling a 17% sales increase. Anika’s leadership transformed the Stiletto team from a liability into a high-performing asset, inspiring other teams to seek her expertise.

Which gives you a clear understanding of Anika’s contributions? Which one do you care about? Which one is more memorable? I bet your answer to all these questions is, “the story”!

Notice also that the story showcases vital contributions that are invisible in the first version: leadership and soft skills, aided by basic knowledge of Scrum. In performance reviews, resumes, and interview answers, these “how” items (your personal contributions) are as important as the “what” items (achievements), yet people often leave them out because they’re hard to measure. The Three-Act Structure’s Act II ensures you cover the “how”.

What if your three acts are too long? Shorten them! AI tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude can help you start and improve your writing and make it more concise. As an example, I gave Claude Opus the following prompt: “Shorten the following story to a single paragraph with no more than three sentences while preserving the three-act narrative structure.” Here’s what it came up with:

The Stiletto team was in crisis, missing all deadlines and dragging down company sales with their inefficient processes. Upon joining the team, Anika methodically introduced Scrum practices like sprint planning and retrospectives, using data to demonstrate progress and win stakeholder support. Her leadership transformed the team's performance, achieving 85% on-time delivery (up from 0%) and contributing to a 17% sales increase, making them a model that other teams sought to emulate.

The longer version captures more detail about what Anika did, but this shows that even if you face tight word limits, the Three-Act Structure can still work.

One last comment about this example: when writing professional stories, you can use impersonal passive voice (“These things were done”), third-person (“Anika did these things”), or first-person (“I did these things”). Since the whole point of these stories is to showcase your personal achievements, avoid passive voice as it conceals who did the work. Choose between first- and third-person based on your situation: first-person feels more personal but can sound boastful if overused, while third-person works well when writing for others (like your manager) to submit. I usually prefer third-person because I find it more comfortable to talk about things “Forrest” did than to keep saying “I”, “I”, “I” all the time. This leads us into the next topic…

Cultural Issues and the Art of Humble Storytelling

Many of us feel uncomfortable “tooting our own horn,” particularly those from cultures that value modesty and collective achievement. You might worry that telling stories about your work comes across as bragging or self-promotion. This discomfort is valid and widely shared—I hear it all the time and feel it myself.

However, there's an important distinction between bragging and communicating your contributions. Effective storytelling isn't about claiming personal glory; it's about helping others understand the value you bring to the organization.

In recent years, there’s been a lot of talk about how it’s useful to build your own “brand” as part of developing your career. A personal brand means when people hear your name, they associate it with your accomplishments and “super powers”, the things you’re good at. I recently came across a quote from Ola Brattvoll, head of Sales and Marketing for Mowi, the world’s largest salmon farming company, that captures an important point: “A brand is a commodity with a story”. The message is, if you’re not telling your own story, you risk being seen as a commodity.

Here are some techniques for telling your story that can help it avoid coming across as boasting:

- Acknowledge team contributions while being clear about your specific role. For example, “Working with the engineering team, I began an initiative to...”

- Focus on your impact rather than personal praise. Instead of saying “I brilliantly solved this problem,” say “This solution reduced customer complaints by 40%.”

- Use data and concrete results to let the facts speak for themselves. Numbers and measurable outcomes feel less like boasting and more like reporting. Be sure your Act II explains how you achieved those numbers, though.

- Frame your stories around helping others. Emphasize how your work benefited your team, customers, or organization.

How You Can Bring Order From Chaos, Today

As humans, we use stories to make sense of the world around us. If you don’t tell your own story, readers will create one about you from whatever raw facts they have. Will they get it right? Will they have time? Will they understand? Will they care? It’s much better for you to tell your story yourself, and base it on what you know is important to them.

Here are some actions you can take now to apply these ideas:

- Pick your most recent significant project and write a short three paragraph story about it using the Three-Act Structure. Focus on:

- Act I: What problems existed before you began?

- Act II: What specific actions did you take to fix those problems?

- Act III: What measurable results did your work produce?

- Review your resume and LinkedIn profile. Replace any passive phrases like “helped with” or “participated in” with action verbs that make your contributions clear.

- Start keeping a “wins journal”. Each Friday, spend five minutes documenting your achievements from the week, including metrics and stakeholder reactions. This way you will build a library of stories you can draw from later.

- Identify a few key artifacts from your recent work (presentations, documents, dashboards, recognition emails, etc.) that best demonstrate your impact. Keep links to these handy to use as “illustrations” for future stories you’ll tell about your work.

- Before you next interview for a job, think of stories you could tell about your experience that would illuminate your expertise relevant to the job you’re applying for. Write out short three-act stories for each to help you think through what you could say about those experiences. When an appropriate question is asked (e.g. “Tell me about a time when you demonstrated leadership”), respond with a fitting story.

Want to Learn More?

- What is The Three Act Structure — And Why It Works, by Alyssa Maio

- Storytelling that Moves People, Harvard Business Review, June 2003, by Bronwyn Fryer (free registration required). How to use storytelling in a business environment.

- How to Tell a Story: The Essential Guide to Memorable Storytelling from The Moth (Amazon affiliate link). If you’ve never listened to The Moth Radio Hour podcast, I highly recommend it. The Moth is an organization that teaches ordinary people how to tell their stories; this book is about their process.

- Structuring Your Novel: Essential Keys for Writing an Outstanding Story, by K.M. Weiland (Amazon affiliate link). Goes into depth on the classic Three-Act Structure.

- The Bunny Narrative for Tech Promo Cases, by Kurt Brown. A fun way that's been used to apply these same ideas to promotion packets inside Google.

What Do You Think?

I'd love to hear about your storytelling experiences! If you're a paid supporter of this newsletter (hint, hint!), you can add comments below.