I Hope This Email Finds You Well: Emailing Senior Executives

Summary

- The #1 skill gap senior executives call out in their teams is the need for better email communications.

- The key to writing clear, concise, and actionable emails is to put yourself in the shoes of the recipient.

- The subject line needs to attract recipients to be interested in opening the email, and the first paragraph of the email needs to succinctly explain what you need, and when you need it by.

- The rest of the email should provide the recipient with key background information they need, and that’s it. Don’t distract the reader from your core message.

- AI tools can be easy to use, yet powerful, aids to improving your emails.

Hot Take

Over the last couple years my job responsibilities included figuring out how to make Technical Program Managers (TPMs) at Google more effective, and I’ve had quite a few conversations with Google directors and VPs about where they saw gaps. I’d always ask those senior executives for their opinion: what set of skills and behaviors did they think my team and I should prioritize? Their answer was always the same—communications skills, particularly the ability to write effective emails. They’d often go on to tell me that while TPMs are expected to be great communicators… could I please see what I could do on this front for engineers and other roles, too?

Maybe you weren’t one of the few people those senior execs weren’t talking about… but chances are, you were. Think about that: senior people several levels above you are saying their biggest skill-based complaint about you (probably you) is that they wish you were better at writing those emails you send them.

I’ve spot-checked this with senior people I know at other companies and industries; it seems execs wishing for better emails isn’t a Google thing, or even a tech thing!

Who Are These “Senior Executives” of Whom We Speak?

The way I’m using “senior executive” in this article is with a little bit of artistic license. You’re probably thinking “directors and VPs”, and yes, I am talking about them… but the core principle I want to get across actually should apply to almost anyone you're emailing who isn’t an immediate collaborator. All these recipients tend to have the following in common:

- You need to let them know something, or to do something for you

- They’re not familiar with the details of the work you’re doing

- They trust you to do your job and don’t have the time (or interest) to learn about all the fine details themselves

While these may not apply to people you’re working closely with, just about everyone else will want the same thing senior execs want: that you get straight to the point and to make it easy for them to get back to you with what you need.

So, even though everything here applies more widely, throughout this article I’m going keep calling these folks “senior executives” because I find that brings connotations that help put me in the right state of mind when I write emails.

How Your Email Really Finds Your Reader

You can find lots of online style and etiquette guides about email, with many bullet points of “do” and “don’t” advice on how to write effectively... but I think they generally miss the forest for the trees (so to speak 😜).

That is to say, don’t just begin your email with the stock phrase “I hope this email finds you well”, but rather, start by asking yourself: how will my email find them? Before your write an important email to an executive, try to think about:

- What’s their workflow like for incoming email?

- What kind of knowledge will they have about the the thing I'm writing to them about?

- What do I expect them to do?

- How will what I’m asking align with their own priorities?

Executive Email Workflow

When I applied for my first job out of college, I wasn’t interviewed—I was applying for a special “executive development program” and so instead I was put through an “assessment center” process. Assessment centers are a deep rabbit hole of their own; briefly, they evaluate candidates by having trained observers watch their behavior in various simulated activities, alone and in groups (yes, that’s exactly as stressful as it sounds!). One of the simulations they used with me was an “inbox exercise”: psychologists had data showing that successful executives had certain patterns in how they processed incoming mail, and so they wanted to watch job candidates so they could select the job seekers who already handled mail that way. They didn’t tell us that’s what was going on: they just gave us a simulated inbox and told us to go through it, handling all the incoming mail in whatever way we saw fit. Then they pull out their stopwatches (seriously!) and say “go!”.

Later I found out that the pattern they were looking for, the one they had found was predominant in effective executives, was simple: only touch each message once. When you open a message, you should skim it quickly and then do one of: (a) make a quick response, (b) forward and delegate it to someone else, (c) put it in your “work for me to do later” folder, or (d) delete it. If a candidate wasn’t decisive about how to handle a message, or if they kept re-thinking things and going back to messages repeatedly (especially unpleasant or hard ones), they failed, and didn’t get the job (somehow, I got the job).

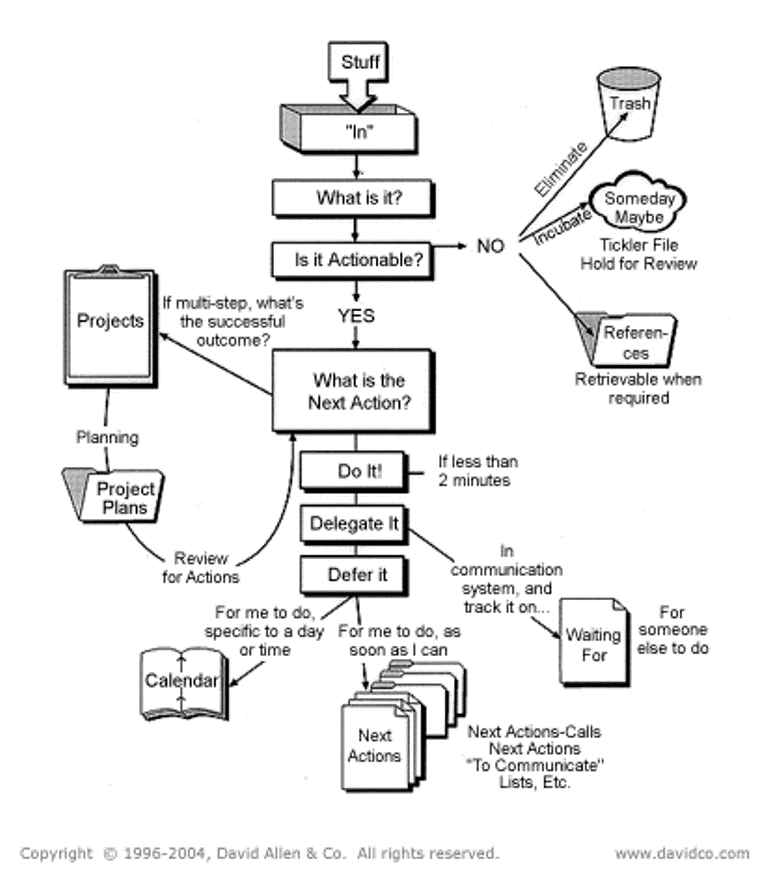

Much later, I found out that this approach has been nicely documented: it’s David Allen’s “Getting Things Done” (GTD) system: there are books [affiliate] about it, classes, even apps for your phone… it’s an effective system that’s well-supported, and lots of people use it. Here’s a flow-chart summary of GTD:

I’ve observed that most senior executives don’t do strict GTD, but almost all of them use a personal system that’s GTD-shaped: they try to touch each message just once, handle each one quickly, and move on. Bear in mind: senior people get a lot of email; they don’t have time to savor each one, to think through the ideas and implications carefully, to dig deeper by doing research and calling up co-workers to see what they think. There are exceptions of course, but broadly speaking, because of the way GTD and GTD-adjacent processes work, if you don’t want to end up in the “someday maybe” category (or worse, the “delete” category), you have to make things easy for the reader:

- The subject line needs to get them to click to open your message

- The first paragraph must make it very clear what you need from them, and when you need it by (the “What is it?" and “Is it Actionable?” boxes in the diagram)

- You need to present the relevant information they need quickly and concisely (so they can easily carry out the “What is the Next Action?” box)

- You need to avoid putting content in your email that will create any confusion, or require more work to parse, in any of the above steps

Let’s take these one at a time.

IMPORTANT! PLEASE READ! (The Subject Line)

Speaking about the importance of book cover art choices, bestselling author James Patterson once said that “No book was ever bought that wasn’t picked up first”. The same is true of email: you’re writing to someone that gets far more email than they can spend time with (yes, including quite a few with unhelpful subject lines like “PLEASE READ”), and you need your subject line to catch the recipient’s attention so they'll click it.

Your mileage may vary, but I’ve gotten good results with using subject lines that both capture the essence of what the email is about (e.g. “Approval Needed for New Fire Alarm System”), and state it in an unexpected way that causes people to pause, and maybe even smile, when they see it (e.g. “Smokey Says: Only You Can Approve Our New Fire Alarm System”).

There are lots of “tricks” you can use, like putting emoticons in your subject line (I’m sure I’d never do that...), but be careful of alienating the recipient with too many gimmicks.

Don’t Bury the Lede: The First Paragraph

I vividly remember a Google VP who explained to me how they read their email: almost always on their phone, moving between meetings, or in brief pauses waiting for their next meeting to start. They told me they have to deal with their email quickly, and when they open a message, because of the small size of their phone’s screen, all they could usually see was the first paragraph of the message. They didn’t have time to scroll back and forth and try to figure out what they were supposed to do with it—the VP told me that if they couldn’t tell what they needed to do with it right then, they’d close the email and maybe get back to it late that night, when they were tired... or maybe on the weekend. Maybe. If you wanted a timely response (perhaps any response) from that VP, the whole point of your message needed to fit within a short first paragraph.

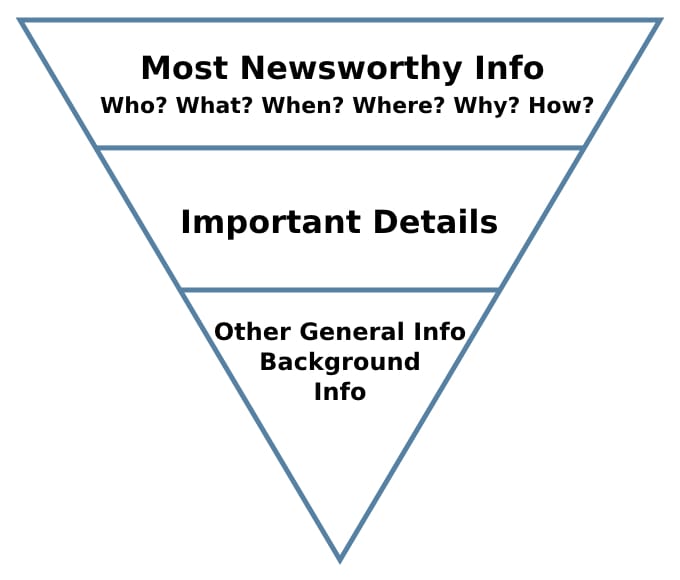

Journalists have a related problem—they don’t know how much of their story their editor will decide to use: because there’s only so much room for content, their story might be cut off after a few paragraphs… or even after just one paragraph! Even if the editor wasn’t a problem, readers get bored and, at some point, stop reading and move on to another story. To deal with this, journalists evolved the “inverted pyramid” style of writing:

Your first paragraph corresponds to the top layer of the inverted pyramid: if they saw nothing else (like my VP reading email on their phone), would they have the most important part of the “story”? There’s another term from journalism that applies here—they call hiding the most important information deep inside a story “burying the lede”.

So if we’re going to put the most important info into that first paragraph, what should be in it? We talked about putting yourself in the reader’s shoes: do some role playing: if you were the recipient, what would you want to know? It will vary by topic and person, but generally, you’d probably want to know:

- Why are they sending this at all? To provide information? To ask for approval? To ask for work to be done?

- What are they sending it to me? Is this something that requires my time and attention, or should someone else be dealing with it?

- Why is it important? Why should I care?

- Do I need to do something? If so, what, and by when?

We Need to Go Deeper: Relevant Background Information

Like newspaper stories, there’s certainly more you need to say than will fit in your opening paragraph. The trick is to balance providing enough background to help the recipient take the action you want, against giving them so much detail that they tune out and dump your email into the dreaded “Someday Maybe” bin.

How you handle this balancing act will depend on your own style and situation, but as an illustration I’ll offer how I do it. The best approach for me is to embed the “how much detail” question in my email writing process:

- I start by writing down what I want to convey in a natural form. I do a lot of my thinking as I write, so this draft form tends to be w-a-y too long, but it’s where I start.

- I look at the whole thing I just wrote and ask: if I could only send a single paragraph, what would I extract out of what I wrote? I make sure I cover just the points outlined in the previous section and turn the result into my new opening paragraph.

- I look at the long draft email again, in light of that new opening paragraph. “Ok, self”, I say to myself, “what’s the minimum that’s in the draft that needs to be included so the reader has what they need to make good decisions about the first paragraph?” As part of this I ask myself what the reader already knows, and avoid repeating that. I can usually fill in the gaps from the first paragraph with one or two background paragraphs. I put those into the email... and that’s where I stop.

- I almost always have a lot left on the “cutting room floor” when I’m done with step 3. A principle I always try to follow is “minimize the surface area of your argument“: everything I have left over is true and interesting (well, to me, anyway), but tends to distract from the main thing I’m trying to communicate, so I try hard to leave it all out. Occasionally I'll link to a longer background document on the off chance the recipient really does want more information... but (surprise!) almost no one ever clicks through to read those docs!

An Example: the Right Way, and the Wrong Way

Let’s put these ideas together. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of a “bad” email, on the left, and a rewritten “good” version, on the right:

| Original (Bad) | Revised (Good) |

|---|---|

|

Subject: Problem with ORM Library for Zeus Project

Dear Priya, I hope this message finds you well. I’m writing to you today because of a problem with the Zeus project. As I'm sure you no, this project is critical to our entry into the competitive call center market. The target is to launch in for months, but we’re concerned that might not be done without your help. The storage layer of Zeus is based on an open source ORM library that we decided to use because it could interoperate more easily with our PostgreSQL database than other libraries we considered. We implemented the Zeus backend successfully, but in testing we found a problem that we traced to a several bug in the ORM library. Unfortunately, none of our engineers has any experience with the internals of this library. We estimate it will take 4 weeks to get an engineer up to speed on it to the point where they can resolve the problem, which is likely to take a further 3-4 weeks. To help avoid this situatin in the future, I'd like to set up a time when you could come talk to our team about the work you did on ORM systems earlier in your career; I think our engineers would benefit from hearing your experiences and insight, and it might motivate some of them to learn more about the internals of how these important componets work. Is it ok if I work with your admin to set up a session like this? Returning to the problem at hand, again, we'd like to take a different path that will allow us to resolve the problem more quickly: we’d like to hire one of the maintainers of the ORM library to do the work for us, as a contractor. We estimate that would could be done in 2 weeks. Nothing is free, of course, wed have to pay a consulting fee to the engineer we contract to do the work, an amount we estimate as $10,000. Zeus project isn’t budgeted for more expense. May I ask you consider approving this additional expenditure for us? We know budget is hard to come by and don’t make this request lightly. We’ve gone back and forth looking at the pros and cons; it basically coms down to time versus money, and right now we don’t have the time if we want to hit our product launch date. Thank you. |

Subject: Urgent Budget Approval Needed to Avoid Zeus Project Delay

Priya, I need your approval by [date] for an unbudgeted $10,000 contractor expense to prevent a critical delay in the Zeus project launch. We've encountered a bug in a key open-source library that impacts our timeline. • Internal Fix: Our team could resolve it, but this would push the launch back. • Contractor Solution: Hiring a library maintainer would address the issue significantly faster. Please let me know your decision by [date]. If this expense can't be approved, we'll need to move forward in using our current team, which will result in a launch delay. Thanks! |

I think the comparison of these two emails mostly speaks for itself, but there are a few points I’d like to highlight:

- The original email fails the cellphone screen test (spectacularly)—you have to read and think through the whole message before you understand what the author needs.

- There’s nothing in the left column that's false... but there’s a lot that is irrelevant to what the recipient needs to decide. Does the recipient really need to understand that the problem is in the ORM layer and how it interoperates with Postgres?

- That first email actually has two “asks“, not one—there’s the urgent need for funding approval, and there's a very low-priority request for the recipient to do a tech talk for the team buried in the middle. If the reader was skimming the mail quickly (and it's pretty much guaranteed they will be!), they could come across this secondary request halfway through the email and think that's what it was all about, and stop there! Seriously, I have loads of “anecdata“ showing that if you ask an exec more than one thing in an email, 90% of the time they'll respond to just one of the requests... and it will usually not be the one you actually needed them to respond to.

- The email on the left has loads of spelling and grammar mistakes. The surface message gets through (eventually), but incorrect English can create a subconscious message that travels in parallel that can distract the reader and threaten the credibility of your main message.

AI Can Make This Easier

Blaise Pascal once wrote to one his correspondents saying “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” That gets to the center of this topic: it’s harder to write a short, concise, easily actionable email than it is to write something long and difficult to decipher. It's also important to note that people's skill with writing English correspondence doesn't reflect the importance of what they have to say, and ensuring the use of language doesn't detract from the message can be a bigger headache for some people than others.

Fortunately, we’re living in the future, and we have artificial intelligence tools that can help us with all of this! Just as no one would think of not using spelling- and grammar-checking features in this day and age, we’re now at a point where I believe no one should think twice about using AI to improve their writing.

Demonstration: I wrote the “bad” email in the previous section of this article myself... but I didn’t write the “good” version: the good example was written by Google Gemini! (How's that for burying the lede?) Here’s the prompt I used:

<Gemini’s gears turn and lights flash; it provides a summary of this article>

Using the principles outlined in that document, please re-write the following email:

<I inserted the text of the original email here>

In seconds, with no more instruction than that, Gemini was able to convert a lengthy, confusing email peppered with spelling and grammar errors and irrelevant information into a concise email with a clear call to action.

ChatGPT can do this as well, but the free version doesn’t have the ability to ingest outside documents the way Google Gemini can. For premium supporters who also have access to ChatGPT Plus, I’ve set up a "custom GPT" that’s been trained on this article and is ready to go immediately, helping you improve your executive emails. Premium supporters can access this AI tool by clicking here.

[Important: You are, of course, responsible for your own compliance with whatever policies your employer has in place. In particular, please consider your company’s policies about exposing proprietary information to AI tools. There may be some tools that are acceptable to your company, and others that are not. Consider steps like changing names and numbers in your email to reduce sensitivity to these concerns, and whether those steps are sufficient.]

How You Can Bring Order From Chaos, Today

Here are some things you can do now to apply these ideas:

- In the next important email you send to someone who isn’t an immediate co-workers, try role playing as the recipient, and ask yourself: how will my email find them? See if you gain any insights into how you could modify your email to be more effective.

- Try sharing a draft of an important email with a friend; ask them to role play the recipient, and then to give you feedback: was your email clear and actionable? Do they know what they need to do, and by when? Do they have any questions before proceeding that your email didn’t answer? Sometimes an outside opinion can be invaluable in providing insight into how to improve communications.

- Play around with AI tools and your own emails. You’re welcome to train it with this article, but also try formulating your own principles, and training it with those.

Want to Learn More?

- Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity, David Allen, 2015 [affiliate]

What Do You Think?

I'd love to hear about your experiences with writing emails to senior executives! If you’re a paid supporter of this newsletter (hint, hint!) you can add comments below.